by Robert D. Kenney

Installment 7 in this series on the marine mammals of Rhode Island was supposed to be on harp seals, but recent events have forced us to let the beluga cut in line without waiting its turn. In June, on the afternoon of Father’s Day, two different belugas were sighted in our local waters. Dale Denelle, a local real-estate broker and fisherman, was fishing for stripers in the West Passage between Whale Rock and Beavertail, when he saw something unusual coming toward his boat. He managed to shoot some cell-phone video, which he posted on line (HERE on Vimeo). Better yet, he correctly identified the animal as a beluga, recognized that it was not the usual thing one might see off the Narragansett shore, and sent word of his sighting to the Graduate School of Oceanography. What Dale had spotted was the first-ever documented occurrence of a beluga in Rhode Island. We found out later that another fisherman had seen a beluga in the Assonet River near Fall River on the same afternoon. Although it was in Massachusetts, it had to swim through Rhode Island waters to get there or to leave.

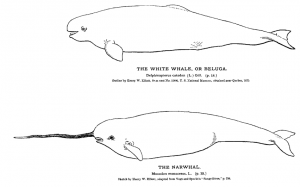

Belugas are also known as white whales; the word “beluga” or “belukha” comes from the Russian word for “white.” Belugas and narwhals together comprise the family Monodontidae; which is closely related to the dolphin and porpoise families. Belugas and narwhals are both found almost exclusively in the Arctic. (LINK to the really terrific narwhal book just published by nature writer and RINHS board member Todd McLeish) They are the last survivors of a family that was formerly more widespread in Northern Hemisphere temperate latitudes. Belugas occur all around the Arctic Ocean—in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Svalbard, Norway, and Russia—in 29 separate, identified regional populations or stocks. Stock differentiation is likely maintained by strong “matrilineal habitat fidelity”—animals return to the same summering habitats that they first visited with their mothers. Two of the stocks—in Cook Inlet in southern Alaska and in the St. Lawrence River and Estuary in southeastern Canada—are referred to as “relict” populations. They were apparently stranded in those estuarine systems as the glaciers retreated at the end of the last Ice Age, and now are totally isolated from all of the Arctic beluga stocks.

Belugas are also known as white whales; the word “beluga” or “belukha” comes from the Russian word for “white.” Belugas and narwhals together comprise the family Monodontidae; which is closely related to the dolphin and porpoise families. Belugas and narwhals are both found almost exclusively in the Arctic. (LINK to the really terrific narwhal book just published by nature writer and RINHS board member Todd McLeish) They are the last survivors of a family that was formerly more widespread in Northern Hemisphere temperate latitudes. Belugas occur all around the Arctic Ocean—in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Svalbard, Norway, and Russia—in 29 separate, identified regional populations or stocks. Stock differentiation is likely maintained by strong “matrilineal habitat fidelity”—animals return to the same summering habitats that they first visited with their mothers. Two of the stocks—in Cook Inlet in southern Alaska and in the St. Lawrence River and Estuary in southeastern Canada—are referred to as “relict” populations. They were apparently stranded in those estuarine systems as the glaciers retreated at the end of the last Ice Age, and now are totally isolated from all of the Arctic beluga stocks.

The total abundance of beluga whales worldwide is estimated to be at least 150,000. Belugas are not listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act or on the Rhode Island state list, and are classified as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List. The St. Lawrence Estuary stock has been estimated at 1,000–1,200 whales and is listed as Threatened under the Species At Risk Act in Canada.

Belugas are taken by subsistence hunters in many parts of the species’ range, including northwest Alaska. In the St. Lawrence estuary, they were hunted for over 400 years until the hunt was prohibited in 1979. The peak years of the St. Lawrence beluga hunt were 1880–1950. The St. Lawrence beluga population may have been as large as about 5,000–10,000 at the beginning of the 20th Century, declining to only about 350 individuals in the 1970s.

A serious concern with St. Lawrence estuary beluga whales is the issue of toxic contamination and associated health effects. The St. Lawrence River is the outlet from the Great Lakes and a substantial watershed in the industrial center of North America. There are contaminants in the water and sediments, accumulating up the food chain to the belugas at the top. St. Lawrence belugas have much higher loads of many contaminants than Arctic belugas. The effects of these contaminants include direct toxicity, suppression of the immune system, effects on the reproductive system, mutation, and cancer. Over a third of all known tumors recorded from cetaceans have been in St. Lawrence River belugas.

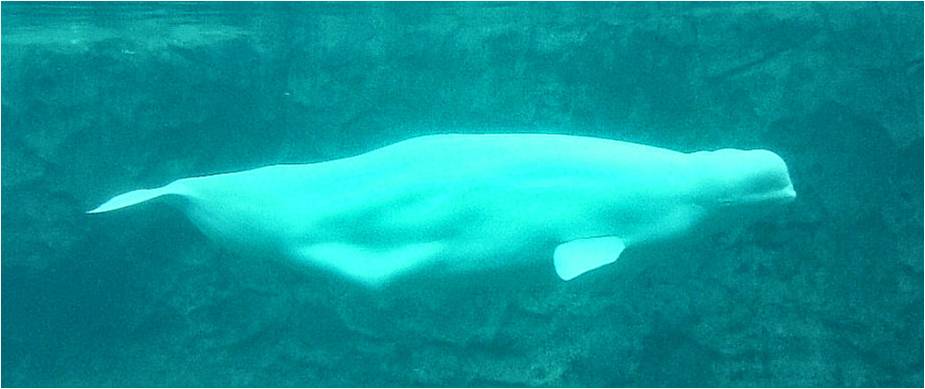

Description: Beluga whales may be the easiest cetaceans to identify (or it’s a tie with killer whales). Adult females are up to 4 m long. The maximum recorded size for a male was 6 m, but they usually do not reach more than about 4.5 m. Belugas have stocky bodies with no dorsal fin, instead there is a low dorsal ridge about 50 cm long but only 1–3 cm high along the mid-back. There may be thick folds of blubber, especially along the ventral surface. There is an obvious neck, which is much more flexible and mobile than in other cetaceans. The head is rounded and tapered in calves, with only the slightest indication of a beak. The melon expands with age, creating a bulbous forehead and a more obvious short, broad beak. The flippers are broad, blunt, and flat, but develop a distinct upward curve on the lateral edge in adult males that can be used to differentiate sexes in the field. The flukes have convex trailing edges. Belugas’ most conspicuous character is their color—adults are completely snow-white. Calves are born dark slaty gray and gradually become lighter with age, becoming all white at the time of sexual maturity.

Description: Beluga whales may be the easiest cetaceans to identify (or it’s a tie with killer whales). Adult females are up to 4 m long. The maximum recorded size for a male was 6 m, but they usually do not reach more than about 4.5 m. Belugas have stocky bodies with no dorsal fin, instead there is a low dorsal ridge about 50 cm long but only 1–3 cm high along the mid-back. There may be thick folds of blubber, especially along the ventral surface. There is an obvious neck, which is much more flexible and mobile than in other cetaceans. The head is rounded and tapered in calves, with only the slightest indication of a beak. The melon expands with age, creating a bulbous forehead and a more obvious short, broad beak. The flippers are broad, blunt, and flat, but develop a distinct upward curve on the lateral edge in adult males that can be used to differentiate sexes in the field. The flukes have convex trailing edges. Belugas’ most conspicuous character is their color—adults are completely snow-white. Calves are born dark slaty gray and gradually become lighter with age, becoming all white at the time of sexual maturity.

Natural history: Beluga whales are highly social and gregarious. They generally are seen in small groups of 2–10 animals, although sightings off the northeastern U.S. are usually single individuals. Belugas follow a distinct annual movement pattern. After the spring break-up of the sea ice, they move into summering areas in near-shore waters and in river mouths and estuaries. They frequently occur in extremely shallow water, sometimes barely deep enough to swim. They are apparently capable of swimming backwards, which may help them avoid being stranded by the out-going tide. One hypothesis for using shallow waters in summer is that water temperatures may warm more quickly, providing a thermoregulatory benefit to young calves. In addition, belugas are the only cetacean known to undergo an annual molt. In summer, the entire outer layer of the skin turns yellow and is sloughed off. During the molt, belugas are known to rub themselves on gravel bottoms in shallow water to help scrape off the old skin. In winter, belugas are thought to mainly move offshore with the ice edge, however satellite-tracked radio-tagging has shown them traveling long distances to as far as 1100 km offshore and as much as 700 km deep in the ice pack.

Belugas are capable of diving to the sea floor in much of their habitat. They routinely dive to 300–600 m and are capable of dives to more than 1000 m with durations up to 25 minutes. The diet of beluga whales is extremely broad, although little is known for the winter season. Prey species include benthic and demersal fishes such as flounders, cods, and sand lance; pelagic fish such as capelin, herring, and smelt; migratory fishes like salmon and eels; squid; octopus; shrimp; and benthic worms, clams, and crabs.

Calving takes place in a relatively short period in the summer, with the timing differing slightly between different stocks. Calving peaks in July in the St. Lawrence population. Calves average 1.6 m at birth. Mating takes place in the spring, and the gestation period is 14–14.5 months. Males attain sexual maturity at about age 8, and females around 5–6. Lactation lasts 20–24 months, with the calf beginning to feed on easily captured prey like crabs, worms, and mollusks during its second year. The inter-birth interval for most females is 3 years.

Historical and recent occurrence: Cronan and Brooks in The Mammals of Rhode Island reported no occurrences of belugas in Rhode Island, but stated that “there are records from New Hampshire; Cape Cod, Massachusetts; and Atlantic City, New Jersey; it therefore seems likely that the white whale may someday be seen off Rhode Island.” They turned out to be right about Rhode Island, although they were wrong about Atlantic City. There is a beluga skull in the Smithsonian collection labeled as “from Atlantic City,” however it came from a whale kept on display in a tank there, which had originally been captured in the St. Lawrence River.

Beluga sightings are rare in our region, but individuals who do appear stay for extended periods, usually near the coast. One might expect them more often north of Cape Cod, closer to home, and there was one group of six animals seen for two months in the vicinity of Portland, Maine in August and September 1927. The earliest reliable record south of Cape Cod was a beluga that was seen in Long Island Sound between Orient Point and Mattituck, New York, for four days in June 1942. Two animals, a white adult estimated at 4 m and a gray juvenile estimated at 3 m, were seen by divers off Avalon, New Jersey, on 17 July 1978. The adult was never seen again, but there were multiple sightings of a juvenile around southern New Jersey until September that year—probably all the same animal. In March 1979 a 3 m beluga was chased out of Jones Beach Inlet on the south shore of Long Island by the Coast Guard. It stayed around the area of Jones Beach and east to Fire Island Inlet through October. It might have been the same whale seen the year before in New Jersey. In 1979, there was also a sighting by an aerial survey on 5 July of a group of 3 belugas near the edge of continental shelf south of Hudson Canyon — the only offshore record in the region. In 1980, a single beluga was seen in Jones Beach Inlet and the channels behind the barrier island between 4 and 12 April, and a single beluga was seen off Moriches Inlet farther east along Long Island on 22 June. In 1981 along Long Island, a 3.35 m beluga stranded on 20 May on Gilgo Beach, and another was seen for four weeks beginning in mid-August around Fire Island Inlet. In February 1985, a beluga was seen in the harbor at New Haven, Connecticut. It was repeatedly sighted over succeeding months. On 13 May 1986 it was found dead and entangled in fishing gear in the Sound south of the harbor, however, the cause of death was determined to be from a gunshot wound. The most recent beluga whales in our region prior to this year were in 2003–4 and 2005. A juvenile whale, eventually nicknamed “Poco,” was sighted repeatedly between September 2003 and October 2004 along the New England coast from New Brunswick to Massachusetts. Poco was found dead on the shore near Portland, Maine in November 2004; a necropsy showed that the probable cause of death was infectious disease. Another animal occurred in the Delaware River and Delaware Bay in April 2005, swimming as far upstream as Trenton, New Jersey.

Coming next in Marine Mammals of Rhode Island: Harp Seal

Pingback: Beluga whales spotted in Narragansett Bay

Pingback: Beluga whales spotted at three locations in Narragansett Bay | Narragansett Bay Blog