by Robert Kenney

We’ve reached the point in this series where we need to talk about the differences between a dolphin and a whale. The truth is that there isn’t a real definition; it’s pretty much arbitrary. In general, bigger animals are called whales and smaller ones are called dolphins, but it isn’t consistent. For example, bottlenose dolphins and Risso’s dolphins are both larger than melon-headed whales or pygmy killer whales. To confuse the issue even more, all four of those species taxonomically are dolphins—belonging the same family, Delphinidae. That is also the case with the subjects of this installment; pilot whales are big dolphins.

Delphinidae is the most diverse family of cetaceans, with 17 genera and 38 or 39 species currently recognized. Those numbers will keep changing as additional populations are recognized as separate species and as our understanding of higher-level taxonomy improves. There are two species of pilot whales in the world, the long-finned and short-finned pilot whale. The species are well-defined and mostly geographically separated, however, both occur in the North Atlantic and their ranges overlap in the U.S. mid-Atlantic region. They are also extremely difficult to differentiate in the field, so we are forced to consider them together.

One of two adult pilot whales swimming around in a cove next to the Beacon Rock estate in Newport in December 1983, showing the characteristic bulbous head and heavy dorsal fin. (photo by the author)

All of the large, black, blunt-headed delphinids (including pilot whales, false killer whales, pygmy killer whales, melon-headed whales, and sometime killer whales) are often collectively referred to as “blackfish,” an old whalers’ and fishermen’s term. Pilot whales are sometimes also called “potheads,” referring not to their preferences in recreational pharmaceuticals but to the resemblance of the head to an old cast-iron cooking pot. Their genus name, Globicephala (“round-headed”) also refers to this feature.

Neither long-finned nor short-finned pilot whales are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act or on the Rhode Island state list, and both are classified as Data Deficient on the IUCN Red List. The total abundance of either species of pilot whale in the North Atlantic is not well known. Canadian scientists in the 1970s estimated that there were 50,000–60,000 long-finned pilot whales in the western North Atlantic. A study in the 1990s estimated 778,000 in the eastern and central North Atlantic. Because of the difficulty in identifying pilot whales at sea, off the eastern U.S. the two species currently must be combined for estimating abundance. Based on a 2004 summer survey, the combined stocks of both species between Florida and the Bay of Fundy included over 30,000 animals.

Directed pilot whale fisheries targeting both species have occurred in many places around the world. A drive fishery (where hunters in boats herd an entire group of animals into a fjord or inlet to be killed) in Newfoundland took almost 10,000 pilot whales in 1956 but declined during the 1960s and eventually ended. Small-scale pilot whale fisheries formerly took place in Norway, Greenland, Iceland, Ireland, and Cape Cod, and Inuit subsistence hunters in Greenland still take small numbers every year. A drive fishery for long-finned pilot whales in the Faroe Islands (located in the northeastern North Atlantic between Scotland and Iceland) dating back to at least the 16th Century is the only substantial hunt still continuing in the North Atlantic. It takes several hundred whales per year, with little evidence for any negative impacts on overall pilot whale stocks in the northeastern Atlantic. Short-finned pilot whales were hunted for centuries in Japan, and there are still catches of a few hundred per year.

Pilot whales are also impacted by bycatch in commercial fisheries. In U.S. Atlantic waters, average annual fishery-related mortality during 2009–2013 was 192 short-fins in the pelagic long-line fishery for swordfish, 29 long-fins in the Northeast bottom trawl fishery, and 1 long-fin each in both the Northeast sink gillnet and midwater trawl fisheries.

Description: Pilot whales are easy to identify, but differentiating the long-finned and short-finned species in the field is exceedingly difficult. Both species are large, robust animals with a distinct “barrel-chested” appearance. Both are sexually dimorphic, with males larger than females. The head is rounded and bulbous with a very prominent melon, a slight beak, and an upturned mouth. The tailstock has prominent dorsal and ventral keels. The flippers are curved, tapered, and pointed. The dorsal fin is low, rounded to somewhat falcate, broad-based, and located well in front of the middle of the body. The color is black, dark gray, or brown overall, except for a whitish “anchor” mark on the chest, lighter gray “eyebrow” streaks from the eyes to the back, and a light gray “saddle” behind the dorsal fin.

Long-finned (top) and short-finned (bottom) pilot whales compared. (Illustrations © Garth Mix, gmixdesigns.com, used by permission).

Long-finned males may be as long as 7.6 m, while females reach a maximum of only 5.7 m. Their flippers are longer at about one-fifth of body length, with an obvious “elbow.” Short-finned pilot whales are somewhat smaller, and possibly slightly more thick-bodied, with males up to 6 m and females up to 5.5 m. The flippers in short-fins are shorter (about one-sixth of body length) and more curved, but the length ranges overlap, making the difference in flipper length nearly useless as a field character for sightings of live animals. In both species, dorsal fin shape changes in older adult males, with a tendency to become more broad-based in long-fins and more broad-based and hooked in short-fins. Additionally, in at least some short-fins, the saddle and lighter streaks on the head may be more distinct, and the overall color more brown than black.

Natural history: Pilot whales live in permanent social groups of about 10–50 animals, but at times pods join to form aggregations of hundreds of animals. Off the northeastern U.S., they commonly associate with other cetaceans. The most frequently observed mixed-species herds in western Atlantic shelf-edge habitats were pilot whales and offshore bottlenose dolphins. They also have been observed associated with Risso’s, common, and spotted dolphins and sperm whales, as well as in the same areas as fin and humpback whales in more inshore waters.

Our knowledge of their diving behavior is relatively sparse. Short-finned pilot whales that were trained by the U.S. Navy routinely dived to 300 m, and were capable of dives of 15 minutes and to at least 500 m and probably over 600 m. In our region, three different long-finned pilot whales have been rehabilitated after stranding and then released with satellite-tracked radio tags. In 1987 three juveniles were released after 7 months in captivity. One of them, a 3-m, 2-year-old male, was tagged and tracked for 94.5 days and a minimum distance traveled of 3144 km. The overall range of dive times was 6 seconds (between breaths at the surface) to almost 28 minutes, with a tendency for shorter dives during the daytime and longer dives at night. Two juvenile males, both tagged, were released in October 1999 after four months in rehab. Most dives were less than 2 minutes and shallower than 15 m, but both whales made dives exceeding 26 minutes. Their deepest dives were 312 and 320 m, which is approximately the depth to the bottom in the area where they were at the time

Much of what we know about pilot whale reproduction is based on information from hunting. In North Pacific short-fins, there are separate southern and northern stocks. In the southern stock, mating is mostly in April–May and births are in July–August, but some births occur year round. In the northern stock calving is more strictly seasonal, with breeding in September and calving in December. Calves are about 1.7 m long at birth. The age at weaning is longer than in long-fins at 3.5–5.5 years, and an older female might nurse her last calf for as long as 15 years. Females reach sexual maturity at 9 years on average and males at about 16 years. From the fisheries in Newfoundland and the Faroes, long-finned pilot whale calves in the North Atlantic are born in July–October at about 1.7 m. Estimates of gestation period range from 12 months to as long as 15–16 months. Calves are weaned at about 22 months, and females that are simultaneously pregnant and lactating are rare. The average inter-birth interval is about 40 months. Females reach sexual maturity at 6–8 years of age and 3.6–3.8 m long and males at about 12–17 years and 4.8 m. Reproductive senescence seems to be less common than in short-finned pilot whales; a pregnant 55-year-old was observed in the Faroes, though ovulations appear to be spaced further apart in older females.

Details of the social structure of long-finned pilot whale herds have been examined by genetic sampling from entire groups killed in the Faroe Islands fishery. All of the adults in a pod are related to one another. The calves and juveniles are offspring of the adult females in the pod, but the pod’s adult males are not their fathers. Both males and females remain with their mothers for their entire lives. It is believed that mating occurs in large temporary aggregations, when the adult males are able to breed with females in other pods. Pilot whales also are one of the only non-human mammals with evidence of reproductive senescence, with post-reproductive individuals contributing to the survival of the young. In this system, the long-term benefits of group-living, social facilitation, and learning are maximized while still avoiding inbreeding.

Both species of pilot whales are known to strand commonly in large groups (“mass stranding”), which occurs only in social toothed whales such as sperm whales, pilot whales, and some dolphin species. The causes of mass strandings are not well understood, and there are numerous hypotheses, including disease, parasites, geomagnetic anomalies interfering with navigation, social cohesiveness, and others. A common site for long-finned pilot whale mass strandings is in Wellfleet on the inside of Cape Cod. The next time you drive out the Mid-Cape Highway toward Provincetown, watch for the sign in the salt marsh saying “Blackfish Creek”—named for the pilot whale strandings that have happened there at least since colonial times. Cape Cod is a good illustration of how multiple causes can interact and lead to a mass stranding. Stranding events there tend to happen in winter, after storms when the water is murky and visibility limited. The bottom slope is nearly flat, so that echolocation provides no cue as to which direction is offshore, which also means that very wide mud flats are exposed at low tide. There is a known area of geomagnetic anomalies. It also may be possible that the usual direction to safety offshore for our pilot whales is south and east, which does not work well inside Cape Cod Bay. In some strandings, rescue attempts are unsuccessful as animals seem to intentionally beach themselves again. Sometimes it appears that one or more individuals may be debilitated by disease or other cause, and the rest of the herd is trying to stay together. The adaptive value of social cohesion may be maladaptive under those circumstances.

The preferred prey of both pilot whale species is squid, although at least long-finned pilot whales have been observed to feed on fish in the North Atlantic. Pilot whales were commonly taken in foreign fishing activities that were conducted in winter and spring during 1977–1991 along the shelf edge off the northeastern U.S., with 391 taken in the mackerel fishery and 41 taken in the squid fishery. It is unclear whether mackerel is an important prey item in winter in our region, or whether the whales were simply feeding opportunistically on mackerel scavenged from the trawl nets.

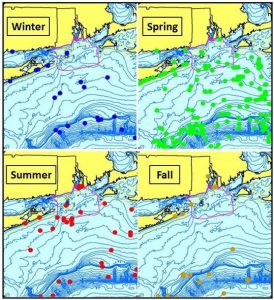

Aggregated sighting, stranding, and bycatch records of long-finned, short-finned, and unidentified pilot whales in the Rhode Island study area, by season, 1834–2006. (from the R.I. Ocean SAMP technical report).

Historical occurrence: The earliest pilot whale records for our region were reported by James De Kay in 1842, who described a stranding at Fairfield Beach, Connecticut in October 1832 and two animals captured at the eastern end of Long Island in 1834. Cronan and Brooks reported three early records from Rhode Island. One pilot whale stranded in Middletown in September 1959 and a 197-cm calf was caught in a fish trawl in March 1961 about 50 km south of Narragansett Bay. The third was “the famous ‘Willy the Whale’ that cavorted about in the upper Providence River in July 1962. ‘Willy,’ who was actually a female, was over 18 feet in length.” There were also multiple stranding and sighting reports from Long Island and Cape Cod, including a very large group of 1,975 seen off Blackfish Creek in Wellfleet in 1895.

Recent occurrence: Pilot whales occur in our area in all four seasons, with a very strong peak in the spring, and roughly equivalent proportions in the other. Sightings were across the entire study area from the inner shelf to the slope, with more in shallow water in the spring, which is most likely related to the inshore spawning of long-fin squid. Although most records are not identified to species, they are almost all most likely the long-finned species. Only one short-finned pilot whale has been identified in or near Rhode Island—a single animal stranded on 6 June 2001 at Snake Hole Beach on Block Island. Otherwise, short-finned pilot whale strandings along the East Coast have occurred only from New Jersey south.

Strandings of single long-finned pilot whales in Rhode Island occurred in Newport in May 1974, in Newport in November 1989 (a 192-cm calf), in Little Compton in April 1990, at Clay Head on Block Island in April 1994, near Goddard Park in Warwick in October 1998, at Third Beach in Middletown in June 2002, at Easton’s Beach in Newport in July 2003, and at Sandy Point on Block Island in May 2004. There were also four strandings of unidentified pilot whales: December 1981 at Apponaug Cove in Warwick, December 1985 at Brenton Cove in Newport, February 1987 in Newport, and March 1987 in Newport. There was one mass stranding—11 long-finned pilot whales in Cow Cove on Block Island on 22 December 1983. The following day only five remained, all dead, but it is unclear from the Smithsonian data record whether the others were pushed off, left on their own, or died and washed out with the tide and waves. From necropsies of the five carcasses by Rob Nawojchik from Mystic Aquarium, the event was not a typical pilot whale mass stranding with a cross-section of ages and sexes. All five were adult females of about the same size (442–457 cm), and all had some sort of medical problems (missing or broken teeth, thin blubber, kidney abnormality, abdominal fluid build-up).

Coming next in Marine Mammals of Rhode Island: short-beaked common dolphin

I was fishing for albies this morning off of watch hill and saw two whales heading east.Im not sure what kind or how big they were but it appeared that they were feeding on something.First time I’ve seen whales that close too boats or buoys or shore.

Today July 26, 2017 I saw for the first time in my adult life here on the Ct shoreline a pilot whale 50 yards off of Watchhill town beach. It seemed healthy although it was alone swimming along at a normal pace blowing water out every three to five minutes. We followed it down the beach to the Watch hill lighthouse.

Pingback: – Marine Mammals of Rhode Island, Part 10, Pilot Whale