by Robert D. Kenney

The bottlenose dolphin may be the most familiar species of cetacean for many people, for a couple of reasons. Small groups of bottlenose can be seen from the beach almost anywhere along the East Coast—year-round from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to the Gulf of Mexico and during the warmer season from Hatteras to New Jersey. And every one of a certain age remembers the Flipper TV series. Nevertheless, this can be one of the most confusing species in terms of understanding their biology, distribution, historical occurrence, etc. One reason is the way that the terms “dolphin” and “porpoise” are often used interchangeably; it may be unclear when a 19th Century publication mentions “common porpoise” whether it’s about bottlenose dolphins or harbor porpoises (the subject of the next installment in this series). And we are still unsure about how many species of bottlenose dolphins actually exist. There have been at least 20 different scientific names applied to them around the world since the first one was published in 1804. Currently, at least two species are recognized—the common bottlenose dolphin and the Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphin, and others have been proposed and are likely to be accepted by the scientific community. It gets even more complicated. In many areas of the world, including the western North Atlantic, there are identifiable inshore and offshore populations. Off the eastern U.S. the inshore and offshore populations are currently considered to be “ecotypes” of a single species, but recent genetic results suggest that they are sufficiently distinct to be considered separate species.

If that wasn’t complicated enough, it gets still worse. Within the coastal bottlenose dolphins along the East Coast, there are multiple stocks or sub-populations that mix very little, if at all. Some of them migrate north and south along the coast with the seasons—such as the “northern migratory stock” that moves north as far as New Jersey in summer and south to North Carolina in winter. Some are more resident within specific areas—e.g., the “South Carolina/Georgia stock.” And some are resident within bays, sounds, or estuaries—29 separate bay/sound/estuary stocks are recognized along the Gulf of Mexico. Federal law mandates abundance estimates for each stock, which has proven to be very difficult. The offshore population was estimated at 81,588 dolphins in 2002–2004 from Florida to Georges Bank. All the coastal stocks along the Atlantic coast include at least 44,000 animals, but several of the estuarine stocks still have no estimates. In the Gulf of Mexico there are at least 35,000 bottlenose dolphins, but again there are no reliable estimates for most of the bay/sound/estuary stocks, or for dolphins in the waters of other Gulf nations.

Bottlenose dolphins are not listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act or on the Rhode Island state list, and are classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. Coastal bottlenose dolphins along the U.S. Atlantic coast were designated as “depleted” under the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1993 because of a significant mortality event in 1987, which killed at least 740 animals over several month. However, the impact of that event was seriously overestimated—the mortality occurred from Florida to New Jersey, but it was compared to the only available abundance estimate at the time, for Cape Hatteras to Delaware Bay New Jersey. “Undoing” that sort of federal designation is a lot harder than doing it in the first place.

Bottlenose dolphins have been hunted in several areas of the world, including the Black Sea, Peru, Sri Lanka, and Japan. There was a bottlenose dolphin fishery in operation at Cape Hatteras, North Carolina at least sporadically from 1797 to 1929, hunting dolphins for meat, oil, and leather. A similar fishery occurred at Cape May, New Jersey in 1884–1885. James E. De Kay and earlier writers described “porpoise” fisheries in the 18th Century or earlier in Long Island, New York. De Kay believed that harbor porpoises had been the targets, but it was much more likely to have been bottlenose dolphins. Bottlenose dolphins are taken incidentally as bycatch in a number of different commercial fisheries around the world. Average bycatch mortality in mid-Atlantic gillnet fisheries dropped from a couple hundred per year to a few tens per year with the establishment of a Take Reduction Plan in 2001. Bottlenose dolphins are also the most frequently stranded cetacean on the U.S. Atlantic coast, with a few hundred dead dolphins every year from New England to Texas.

Description: Bottlenose dolphins are the “plainest” and least distinctively marked of all of the beaked dolphins in the North Atlantic. Body size is extremely variable between populations; adults may be 2–3.8 m long. Offshore animals average about 15% larger than inshore animals along the U.S. Atlantic coast. The body is relatively thick and robust (especially in offshore animals), with a tall, falcate dorsal fin. The beak is well-defined and prominent, of medium length, and stout. The body is basically gray to brownish, darkest on the back and lightest on the belly. There may be a clearly visible darker cape, or the color may simply fade gradually from the back to the belly. In addition to consistent genetic and biochemical differences, inshore bottlenose dolphins in the western North Atlantic are significantly smaller than offshore animals; are usually lighter-colored; have flippers and beaks that are larger relative to body length, as well as narrower skulls and rostrums; feed on different types of prey; and carry different types of parasites.

Natural history: Bottlenose dolphins are gregarious, usually occurring in small groups of around 2–15 animals, but groups larger than 1000 have been reported. They generally are seen in smaller groups in bays, sounds, and nearshore waters than offshore. Off the northeastern U.S., the average group is around 15, ranging from 1 to 350 (combining inshore and offshore sightings). Group membership is dynamic, with sex, age, reproductive status, kinship, and affiliation history all involved. The social structure has been called a “fission-fusion” society. Some subgroups are stable for long terms, some may be repeated over periods of years, and others are more ephemeral. The basic social units are nursery schools of adult females and their calves, mixed-sex juvenile schools, and adult males, either solitary or in strongly bonded pairs and trios. Dominance hierarchies are observed in captivity—maintained by aggressive behaviors, including posturing, loud jaw claps, and physical contact.

There are many reports on the prey of bottlenose dolphins, mostly dealing with inshore animals. The dominant prey are fishes, primarily from three families—sciaenids (weakfish, croaker, spot, etc.), scombrids (mackerels), and mugilids (mullets). They also feed on many other kinds of bony fishes, plus skates, rays, sharks, squid, shrimp, and isopods. Stomach contents of offshore animals are dominated by lantern-fishes and squid.

Female bottlenose dolphins give birth after a 1-year gestation to a single calf that is 84–140 cm long, with substantial differences between populations. Calving seasonality varies between populations; births probably peak in the spring in Atlantic populations. Mothers and calves rarely separate during the first few months. A calf may nurse for several years, but begins foraging independently during its first or second year, maybe as young as four months. A calf is usually weaned completely at around the time the mother gives birth to the next calf, after an interval of 3–6 years.

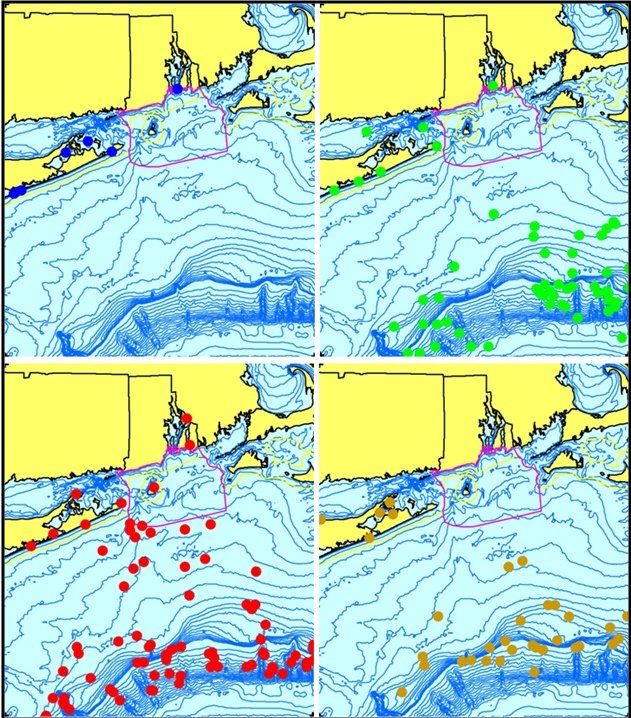

Aggregated sighting, stranding, and bycatch records of common bottlenose dolphins in the Rhode Island study area, 1899–2006 (n = 182: winter[blue] = 8, spring[green] = 57, summer[red] = 83, fall[brown] = 33, unknown = 1).

Recent occurrence: The distribution of bottlenose dolphins off Rhode Island is consistent with what we know from broader studies in the western Atlantic (see the accompanying map). Sightings of offshore dolphins occurred year-round in waters of the outer shelf, shelf break, and upper slope. Summer was the peak season (45.6%), followed by spring (31.3%), fall (18.1%), and winter (4.4%). There were a number of more inshore sightings in summer, but they were still mostly in waters deeper than 40–50 m, so there is no clear evidence for the occurrence of coastal bottlenose dolphins in our area.

It is interesting to speculate about what might happen in the future as ocean temperatures in our region continue to warm. We now know that migratory bottlenose dolphins between Virginia and New Jersey reach the northernmost point their migration at the warmest part of the summer, and range farthest north in the warmest years. We also know that coastal dolphins must have occurred along Long Island historically if they were hunted at Montauk in the 18th Century, although they are scarce there today. With a little more warming, it is possible that we could see bottlenose dolphins swimming along our beaches from Napatree to Point Judith within the 21st Century.

Bottlenose dolphins are the eighth most frequently stranded cetaceans in the Rhode Island study area, which is much lower than their ranking in New York (third) or in New Jersey and states to the south (first). This is certainly due to the northern extent of the range of the inshore population. There have been four bottlenose strandings in Rhode Island in recent years. A 265-cm bottlenose dolphin live-stranded on the shore of Mount Hope Bay in Warren in August 1983, and was taken to New England Aquarium. In August 1992, a 310-cm dolphin (most likely an offshore animal) stranded on the east side of the Sakonnet River in Little Compton. The last two Rhode Island strandings were both in 2004—one on the Navy base in Newport in March and the other on Block Island in July.

Coming next in Marine Mammals of Rhode Island: Harbor porpoise