by Robert D. Kenney

The porpoises are six species of small toothed whales within one family—closely related to the dolphins. The harbor porpoise is the smallest cetacean, and the only porpoise species, that occurs in the North Atlantic. When I was a graduate student, I worked on a project called the Cetacean and Turtle Assessment Program, or CETAP, which involved hundreds of hours of aerial surveys between North Carolina and Nova Scotia. From an airplane flying at 750 feet above the water, a harbor porpoise looks very tiny indeed. The only sure way to tell that you aren’t looking at a tuna or some other big fish is that the tail moves up-and-down instead of side-to-side. They looked so small that some of the aerial survey team took to calling them “sea hamsters.”

Harbor porpoise illustration from Frederick W. True (1889) Contributions to the Natural History of the Cetaceans; A Review of the Family Delphinidae. Bulletin no. 36. U. S. National Museum.

Harbor porpoises are relatively common, are not listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and are classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. A proposal was made by NOAA Fisheries in 1993 to list the Gulf of Maine/Bay of Fundy population as Threatened because of excessive by-catch mortality in the sink-gillnet fishery, but it was withdrawn in 1999 after an extensive review determined that the listing was not warranted. Northwest Atlantic harbor porpoises are listed as Special Concern under the Species at Risk Act in Canada. The total number of harbor porpoises in the North Atlantic is likely to be over 500,000, and the estimate for the Gulf of Maine/Bay of Fundy stock is around 80–90,000.

Harbor porpoises have been hunted in many areas around the North Atlantic for oil and meat for at least hundreds of years and probably much longer, but the practice continues today only by Inuit subsistence hunters in the Arctic. A much greater concern is mortality of harbor porpoises as by-catch in commercial fisheries, especially in sink-gillnet fisheries. The first U.S. government fisheries report in 1886 described the efficiency of gillnet fishing for cod, but also reported incidental captures of harbor porpoises. Since the U.S. marine mammal stock assessment program began in 1995, hundreds of harbor porpoises have been drowned in gillnets off the East Coast every year—over 2,000 in some years. A Take Reduction Plan is in effect in U.S. Atlantic waters (http://www.nero.noaa.gov/protected/porptrp), involving fishery closures in specific areas at times when the probability of porpoise by-catch is high, plus a requirement for the use of acoustic alarms (“pingers”) to alert porpoises to the presence of gear. By-catch mortality has declined somewhat, but not enough. Because of high porpoise mortality in gillnet fisheries off Rhode Island and southern Massachusetts, the Plan includes a “Cape Cod South” closure area that extends from 71°45′ W (approximately the longitude of Weekapaug) east to 70°30′ W (eastern Martha’s Vineyard), and from the shoreline south to 40°40′ N (a little over 50 km south of Block Island). Gillnet fishing is prohibited completely in March, and is allowed in December–February and April–May only using nets with “pingers.”

Harbor porpoises are the most common stranded cetacean in or near Rhode Island. Fishery-related mortality is likely to be a significant factor. Over a quarter of the porpoise strandings where a cause of death could be determined showed evidence of fishery interactions (e.g., rope or net marks). In another 18%, the animals were judged to be emaciated and most likely were newly weaned calves that were unsuccessful at feeding independently.

Description: Porpoises differ from dolphins in several characters. Porpoises have small but robust bodies with relatively small flippers and dorsal fins—all likely related to conservation of heat for a relatively small animal living in cold water. Porpoises have conical heads without pronounced beaks. The front part of the skull is much shorter than in small dolphins, and there is a pair of rounded knobs on the skull just in front of the braincase. Porpoise teeth are small and “spatulate” (flattened and curved, like tiny shovels) rather than conical as in dolphins.

Harbor porpoises are the smallest cetaceans occurring in the North Atlantic, reaching only 1.4–1.9 meters long. Females tend to be somewhat larger than males. The average adult female is 160 cm and 60 kg, an average male is 145 cm and 50 kg, and the largest individual known was a 200-cm, 70-kg female. The body is stocky, dark gray to black on the back and white on the belly with little or no distinctive patterning. The sides may be mottled or simply fade gradually from dark to light. There are often one or more dark stripes from the corner of the mouth to the flipper, and some may show darker eye, chin, and lip patches. The flippers are small and pointed, and the dorsal fin is small and usually triangular.

Natural history: Harbor porpoises are known from cool temperate to subpolar regions around both the North Atlantic and North Pacific, most often in relatively shallow continental shelf and coastal waters. They exhibit a clear seasonal pattern of distribution and movement, however there is little evidence for a coordinated annual migration. Off the Northeast, they are most concentrated in the northern Gulf of Maine and Bay of Fundy in the summer, and show up in the mid-Atlantic in winter. Adults may winter farther offshore than younger animals. Strandings are widespread from Maine to North Carolina.

Porpoise life histories are more like those of baleen whales than those of dolphins and other toothed whales. They mature quickly, grow rapidly, have short intervals between calves, and do not form permanent social groups. The most common harbor porpoise sighting off the northeastern U.S. is a single individual, with pairs and trios common. Occasional sightings of groups of 6–10 or even larger are most likely short-term associations, probably in areas of abundant prey. Reproduction is strongly seasonal, with most calves born in May in the Gulf of Maine. Gestation lasts 10–11 months. Calves are about 75 cm long and weigh about 6 kg at birth, and triple their weight in about 3 months. Lactation lasts at least 8 months, but weaning is gradual and calves begin feeding independently well before being completely weaned. Most Gulf of Maine females mate soon after giving birth, resulting in simultaneous pregnancy and lactation and 1-year intervals between calves. Females typically reach sexual maturity at 3–4 years of age.

Harbor porpoises primarily feed on fish and secondarily on squid and crustaceans. They prefer non-spiny fishes with relatively high fat content that are less than 40 cm long (usually 10–30 cm). Their primary prey species in the Bay of Fundy are herring and silver hake. Other commonly eaten species include anchovies, sprat, sardines, and capelin, and calves apparently begin feeding on small crustaceans.

Historical occurrence: Historical accounts of harbor porpoises in southern New England must be treated with some skepticism because the word “porpoise” has been applied commonly to dolphins, even into the 1950s and 1960s. James E. De Kay in 1842 reported that porpoises were “formerly so abundant on the shores of Long Island as to have induced the inhabitants to form establishments for their capture,” but his account was second-hand—based on a 1792 report describing a net fishery in eastern Long Island taking porpoises for oil and leather. More recent studies concluded that the fishery was not for harbor porpoises, but was most likely for bottlenose dolphins (see the previous entry in this blog series Marine Mammals of Rhode Island).

In The Mammals of Rhode Island (Cronan and Brooks 1968), the authors knew of no records of harbor porpoises in Rhode Island, but did mention occurrences nearby in Mount Hope Bay in July 1931 and September 1934. In the Smithsonian database there is a record of a stranding at Brenton’s Point in Newport on 5 July 1901 and another undated specimen record from Newport, both collected by Major E.A. Mearns. There are also records of a 119-cm, 26-kg porpoise stranded at Narragansett Pier in February 1972, and 139-cm animal stranded on First Beach in Newport in March 1976. There are multiple historical stranding and capture records from New York and New Jersey, and a few from Connecticut and Massachusetts. The earliest harbor porpoise record in our region was a report of a porpoise taken more than 30 km up the Connecticut River in Middletown, Connecticut in 1850.

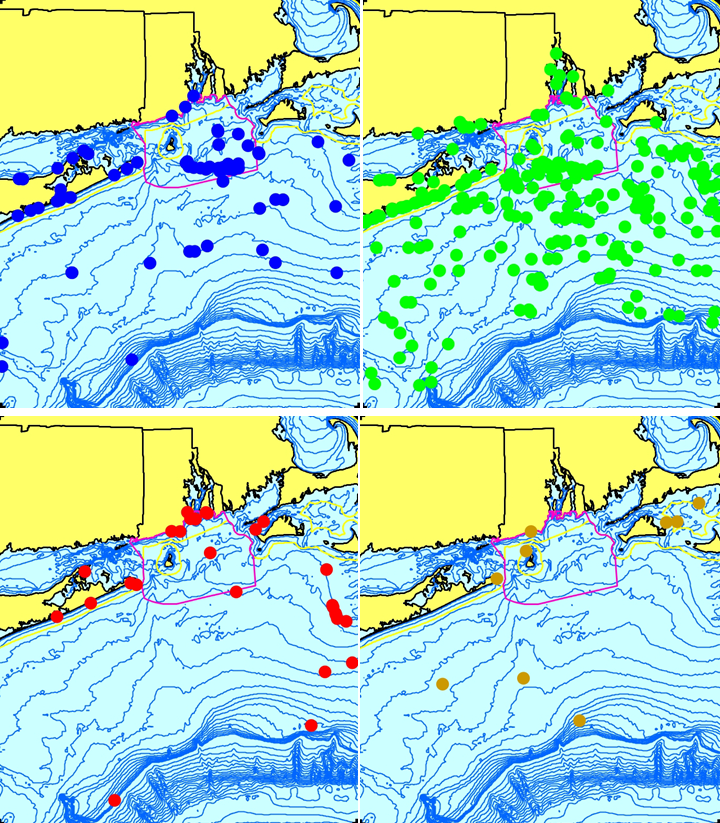

Recent occurrence: Harbor porpoise occurrence in Rhode Island and nearby is strongly seasonal, with 69.5% of all records in spring, followed by winter (19.5%), summer (7.8%), and fall (2.7%). This follows what we know of the population’s seasonal cycle—we see harbor porpoises most often when they are returning from farther south and offshore in the spring, heading for the Gulf of Maine. Sightings are widespread across the shelf. They probably also occur in winter in Narragansett Bay, although we have only second- and third-hand anecdotal reports for evidence. Strandings have occurred all along the south shore of Long Island, along both sides of Long Island Sound, and in parts of coastal Rhode Island. Seasonal stranding frequencies do not quite match the sighting frequencies; they are highest in winter and second-highest in spring. Winter sightings are almost surely biased low—they are hard to see to begin with (small, mainly solitary, and tending to avoid vessels), winter conditions make that even more difficult, and there are many fewer observers on the water in the winter.

Aggregated sighting, stranding, and by-catch records of harbor porpoises in the Rhode Island study area, 1850–2007 (n = 376: winter = 73, spring = 262, summer = 29, fall = 10, unknown = 2).

Coming next in Marine Mammals of Rhode Island: Sperm whale

Industrial overfishing of Atlantic menhaden and Atlantic herring dating back to the 1950’s , has extirpated these small cetaceans from much of their historic inshore range below Cape Cod . These cetaceans were common in the waters surrounding Long Island and like our bottlenose dolphin populations here they have been ” disappeared” by prey deprivation.