by Robert D. Kenney

Gray seals (“grey” seals in Canada and Europe) are the second most likely seal species to be encountered in Rhode Island, after harbor seals (harbor seals are covered in installment 5 in this series). Unlike harbor seals, which are found in both the North Atlantic and North Pacific, gray seals occur only in the North Atlantic. There are three separate populations: a Canadian stock that occurs from Massachusetts to Labrador, a European stock that occurs from France north to Russia and west to Iceland, and a third stock in the Baltic Sea. There are two principal pupping concentrations of the Canadian stock: one in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the other on Sable Island off the southern coast of Nova Scotia (basically a narrow sandbar more than 100 miles offshore—27 miles long but only 3/4 of a mile across at its widest point). The Baltic population is distinctive enough genetically to be considered a separate subspecies.

Gray seals are one of the success stories of the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), although not everyone will agree today whether that was a good thing. They were hunted by Native Americans for subsistence, and then by European settlers for oil, meat, and leather. By the mid-19th Century, gray seal abundance in the U.S. and Canada had been greatly reduced. In the modern era, commercial hunting has been relatively limited because of low abundance and relatively low pelt value. Most modern hunting has been primarily for population control to protect commercial fisheries—reducing sealworm infestation (see further below for details), minimizing damage to fishing gear, and reducing perceived seal consumption of commercial fish stocks. Bounties paid by state authorities in both Maine and Massachusetts were one factor leading to their near extirpation in the northeastern U.S. by the 1960s. When the MMPA was enacted in 1972, gray seals were effectively absent from southern New England.

The recovery of gray seals in New England has been tracked by monitoring the numbers of pups born each year. One pup was observed in Massachusetts in 1969, and absolutely none were seen during the 1970s. In 1988, 5 pups were counted on Muskeget Island, an uninhabited sandy island off the west end of Nantucket. The seals re-colonizing Massachusetts came from Sable Island, the nearest population center in Canada. Counts increased to 59 in 1994, 883 in 2002, and 2095 in 2008, with pupping expanding to Monomoy Island (a National Wildlife Refuge) off the “elbow” of Cape Cod. An additional 515 pups were counted in 2008 at two sites in Maine. By 2010 pupping had expanded to one more site in Massachusetts and two more in Maine. The total number of gray seals in southeastern Massachusetts alone in 2015 was estimated at 28,000–40,000 by applying standard correction factors to counts of seals on the beaches from Google Earth images. Based on pup counts, the number of gray seals in Canada is between 330,000 and 500,000. Needless to say, gray seals are not listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act or on the Rhode Island state list, and are classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

The number of gray seals killed by humans each year averages close to 6,000 for the U.S. and Canada combined, which sounds like a lot but is really not significant relative to the population size. The lion’s share is removal of more than 4,000 “nuisance” animals in Canada. There is a small commercial hunt in the Gulf of St Lawrence (600–700 per year), and a personal hunting license allows Canadians to take up to six gray seals. The average number of gray seals killed per year during 2012–2016 by incidental take in U.S. commercial fisheries was 873, which has been increasing as the population grows (and which includes an unknown mix of seals from U.S. and Canadian rookeries).

As hinted above, not everyone is pleased with the booming gray seal population. An adult male gray seal can weigh as much as 400 kg (880 lb), substantially more than the biggest harbor seals at 170 kg (350 lb). That means two things. One gray seal can eat a lot more fish (and bigger fish) than a harbor seal. And a gray seal is a much more tempting meal for a large shark. The combination of large numbers of fat seals, warming ocean temperatures, and a ban on commercial fishing for great white sharks in U.S. Atlantic waters since 1997 has led to an ever-increasing number of white sharks off the beaches of Cape Cod. The tourism industry is worried that sharks will keep the tourists away, although some tourists are now coming specifically to see sharks and seals. Fishermen are concerned that both seals and sharks are eating “their” fish. There have been calls to ease restrictions in the MMPA to make it much easier to kill “excess” seals, and there has been an apparent increase in seals found dead from gunshot wounds (six on the Cape in 2011).

Description: Gray seals are sexually dimorphic, with adult males up to 2.7 m long and females up to 2.1 m. The sexes also differ in color—males are mainly dark with irregular light patches and females are light with dark spots. Pups are born with a solid white or yellowish coat, and molt to a spotted coat after weaning. Gray seals (including pups) are distinguished from harbor and harp seals by the distinctive shape of the head. Gray seals have an elongate snout with a flat or slightly convex profile, in contrast to the shorter, concave, “puppy-dog” snout of the smaller seals. In some areas of Canada and the British Isles they are sometimes called “horsehead seals.” The distance between the eyes and nose is at least twice the distance between the eyes and the ear openings. The neck and chest of males may be wrinkled, scarred, and often devoid of fur—believed to result from male-male fights over access to females. Females tend to be sleeker and lack scarring. The nostrils are widely separated and from the front look like the letter “M” or “W,” while harbor seal noses look more like a “V.” Gray, harbor, and harp seals are easily distinguished from one another by their teeth, particularly the premolars and molars, but looking into the mouth of a live seal to examine its teeth is generally not advisable.

Natural history: Gray seals give birth to single pups in January or February. Pupping can occur in a variety of locations depending on region—rocky ledges (Maine and Nova Scotia), sandy beaches (Sable Island and Massachusetts), and sea ice (Newfoundland). Adult females attend their pups continuously from birth to weaning and do not feed at all during that time, losing up to a third of their body mass. The breeding fast is even longer for adult males, since they arrive first to stake out and defend territories. Pups are weaned and abandoned in about 18 days, followed by a post-weaning fast of 10–28 days. Newly weaned pups are so fat and buoyant that they can’t really swim well. Pups are born with a white fetal coat (lanugo) that is molted around the time of weaning. Ovulation and mating also take place around the time of weaning, which is why the males hang around to guard the females from other males. Implantation of the early-stage embryo is delayed for about 3.4 months, “stretching” the 8-month gestation period into an effective annual breeding cycle.

After the winter breeding season, there is a post-breeding pelagic feeding period in February–April. This is followed by a haul-out for molting in May or June, then another dispersed feeding period until the next winter’s pupping season begins. Tracks of gray seals tagged with satellite-linked radio tags and incidental captures in fishing gear far out at sea both confirm that adult gray seals commonly travel long distances far from their breeding sites on their foraging trips. Juveniles don’t range as far offshore, but disperse widely along the coast during feeding phases of the annual cycle. Like harbor seals, but unlike harp and hooded seals, gray seals haul out routinely for resting and not only for breeding or molting.

Gray seals feed on a variety of fish species and cephalopods (squid and octopus), with no evidence for significant dietary differences between first-year juveniles and adults. Scat samples collected from Muskeget Island included flounder, silver hake, sand lance, skates, and gadids (cod and related species). Species identified from scats collected from Sable Island, Grand Manan Island, and eastern Nova Scotia included sand lance, herring, silver hake, cod, pollack, capelin, flounders, mackerel, and squid. In New York waters, stomach contents of stranded gray seals showed herring to be the predominant prey, as well as mackerel, gadids, and flounders.

The age at sexual maturity differs between the sexes. Most females mature at 4 or 5 years of age. Males mature at 6 years, but do not begin to breed until age 8, when they are large and strong enough to compete with other males. Most breeding bulls are 12 to 18 years old; older males can no longer compete with the younger bulls. The typical lifespan is 25–35 years in the wild, with females living longer than males. The record was 46 years in one wild female.

Sharks are the major predator of gray seals, with a variety of different shark species having been implicated. Greenland sharks are suspected as a principal predator around Sable Island, and we now know that white sharks are their primary predator in Massachusetts. During the molt, adults in Massachusetts probably become more vulnerable to shark predation by spending more time close to shore.

Gray seals are subject to a variety of diseases and parasites, which are better known in harbor seals; it is likely that many of the same organisms affect gray seals. Most disease incidences are known from pups where the immune system has been compromised by starvation, rendering them subject to a variety of opportunistic infections. Common infections include pneumonia, conjunctivitis, and septicemia. External parasites include seal lice and nasal mites. Internal parasites include a variety of roundworms, spiny-headed worms, tapeworms, and flukes in the gut, lungs, liver, and kidneys. Of particular interest is the sealworm or codworm (Pseudoterranova decipiens). The penultimate phase of the parasite’s life cycle is as a large late-stage larva (1 to 1.6 inches long) encysted in the muscle tissue of a fish like cod or haddock, greatly reducing the palatability and marketability of the fillets. Piscivorous seals are the final host in the life cycle of the worms, which mature and reproduce in the seal’s gut. Sealworms can infect other seal species, but are most commonly found in gray seals in most areas. Heartworm (a different species than the dog heartworm) infects many seal species, but has not been found in gray seals.

Historical occurrence: Gray seals were largely absent from Rhode Island and nearby waters until recently. In The Mammals of Rhode Island, Cronan and Brooks reported that the species was unknown from Rhode Island, but said that there was one record to the south. That referred to a report of a juvenile male taken in a net at Young’s Million Dollar Pier in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1931. Archaeological finds indicate that Native Americans sometimes utilized gray seals on Block Island and along the Connecticut coast, however, the number of individuals was apparently relatively small. It is quite possible that the Indians simply made opportunistic use of stranded animals at no greater frequency than current stranding rates. There are no other historical reports in the literature of gray seals in southern New England except for the known breeding colony near Nantucket—which survived into the first half of the 20th Century but had been extirpated by the end of the 1960s.

Recent occurrence: The recovery of the Massachusetts and Canadian populations has led to an increased occurrence of gray seals in southern New England and mid-Atlantic waters. There are gray seal specimens in the Smithsonian collection from strandings in New Jersey in 1973 and 1978. These were the first documented records west of Massachusetts after the 1931 Atlantic City animal. The two earliest strandings recorded in Rhode Island, both from Block Island, were in 1986 and 1988. In 2004, however, I pulled a frozen seal out of the walk-in freezer on the Bay Campus to use as a specimen in a class at the Shoals Marine Lab. It had been hiding in the back of the freezer, wrapped in burlap, for 24 years. Although the tag read “harbor seal, Block Island, March 3, 1980,” when it was unwrapped on the necropsy table it turned out to be a gray seal—the earliest known stranding in the state by six years. The first sighting of a live gray seal in eastern Long Island was in about the same year.

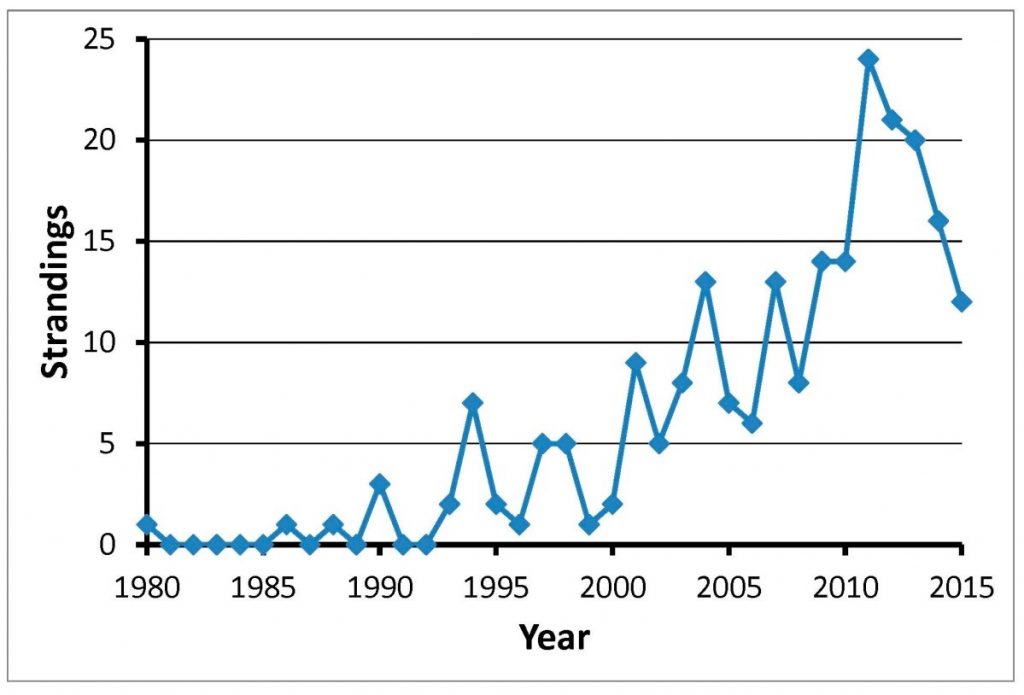

Strandings and occasional sightings throughout the region have become much more common. Numbers of strandings per year began to increase steadily during the 1990s and even more sharply since 2000, reaching a peak in 2011 before four years of decline (I only have the data through 2015, so I don’t know what has happened since). The trend is clearly mirroring the trend in numbers at the pupping beaches in Massachusetts.

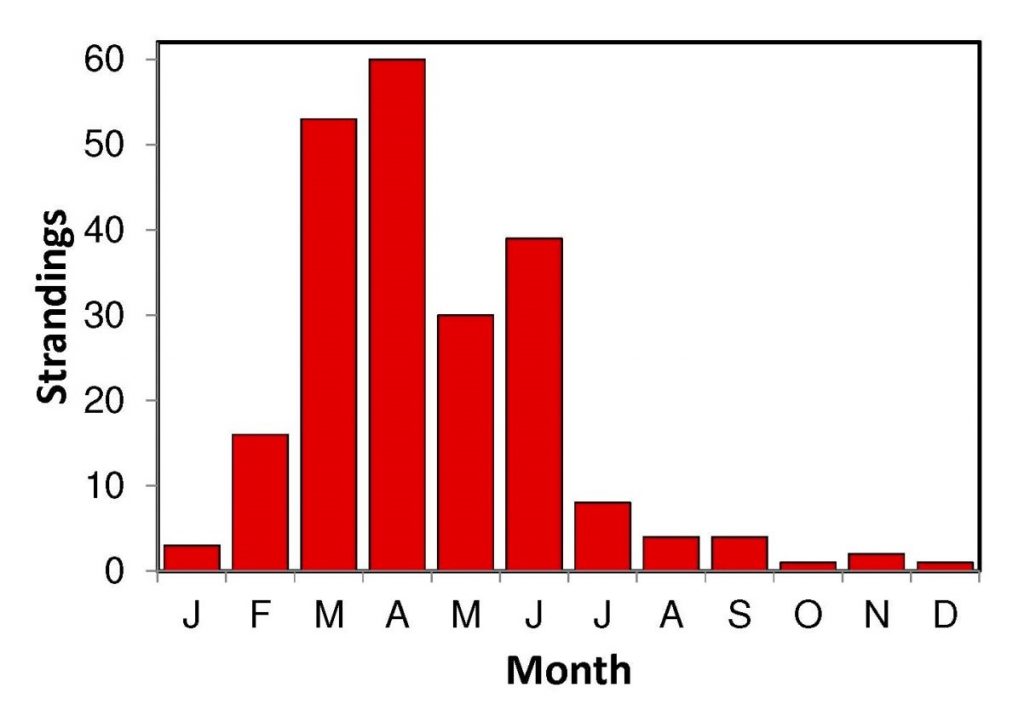

Gray seal occurrences in Rhode Island are almost entirely represented by stranding records. Gray seal records in the region are primarily from the spring, with a peak from March through June. That peak seems to be spreading out more into May and June over the last decade. A monthly tabulation of the regional strandings through 2005 completed for the R.I. Ocean SAMP showed a very sharp peak in March and April, with 75% of all strandings, compared to only 51% in March–April through 2015. The very strong seasonality observed in gray seal occurrence in our area is clearly related to the timing of pupping in December–February. The majority of individuals in the study area appear to be post-weaning juveniles, and starved or starving juveniles are the most common stranded individuals encountered. A young gray seal needs to learn how to find and catch fish totally on its own, with absolutely no help from its mother. The expected period of feeding dispersal by newly weaned pups that have just completed their post-weaning fast and molt would be in March and April.

As with other seals, habitat use by gray seals in southern New England away from the pupping beaches and haul-outs is poorly known. They are seen only infrequently at sea, and very difficult to identify to species when they are sighted in the water. No definitive conclusions about habitat preferences should be drawn from strandings. Gray seals are frequently observed mixed in with groups of harbor seals at haul-out sites in Massachusetts and northward, and occasionally in New York in smaller numbers. Until recently there had been very few observations of gray seals in Rhode Island other than strandings. That appears to be changing. In recent years numbers of gray seals have been remaining year-round on Sandy Point at the north end of Block Island. There were a dozen or so there in October 2018 when we took a field trip to see them during the RINHS Block Island Vacation Week. They seemed to be mostly younger animals. The spreading out of the spring stranding period between 2005 and 2015, from March–April to March–June, is likely a result of the increasing residence of juveniles in our area.

Finally, Block Island’s Sandy Point is very similar in overall appearance to the pupping beaches in Massachusetts, and does not get a lot of visitors in mid-winter during the gray seal breeding season. As the growing Massachusetts population pushes more and more seals in search of new breeding areas, Sandy Point might be a good place for a new breeding colony to be established. I’m looking forward to that day.

Coming next in Marine Mammals of Rhode Island: Risso’s Dolphin

Pingback: – Marine Mammals of Rhode Island, Part 14, Gray Seal