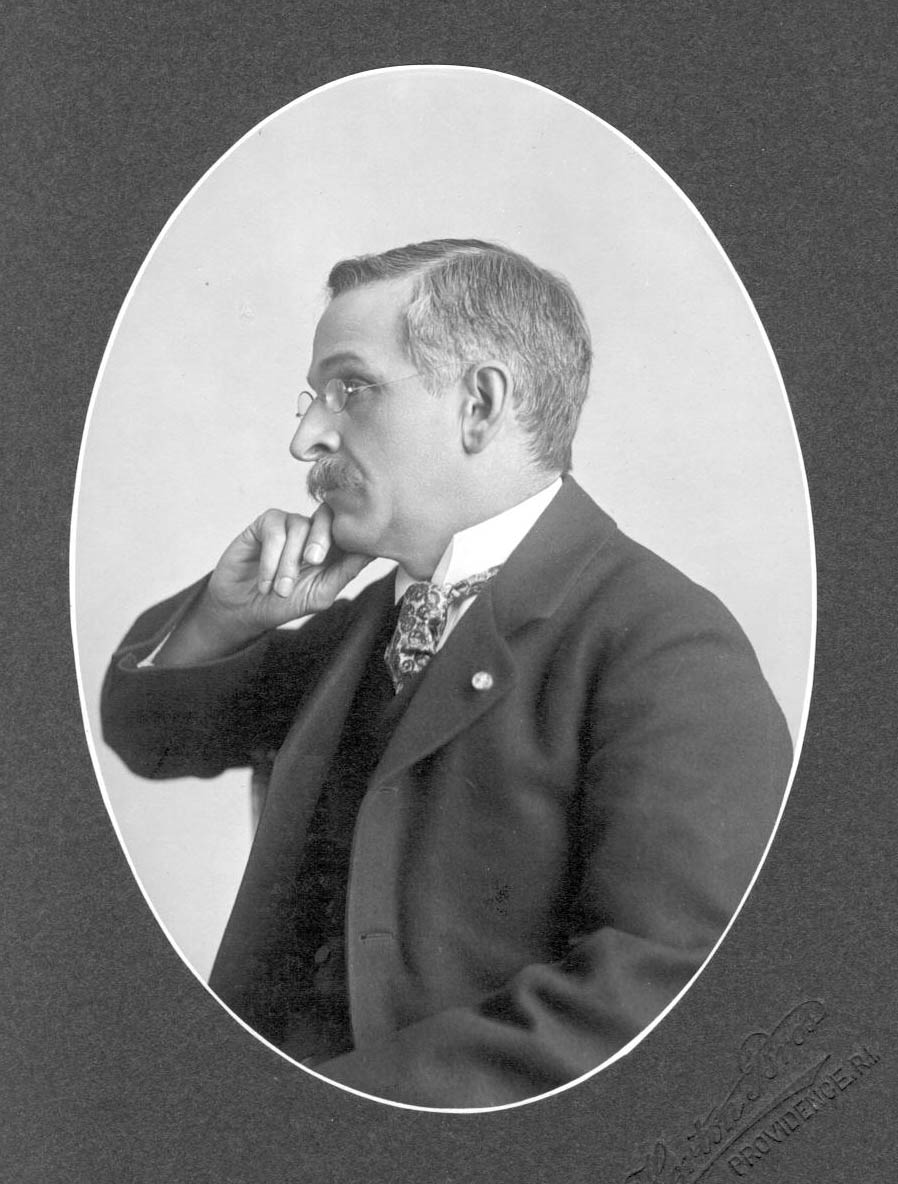

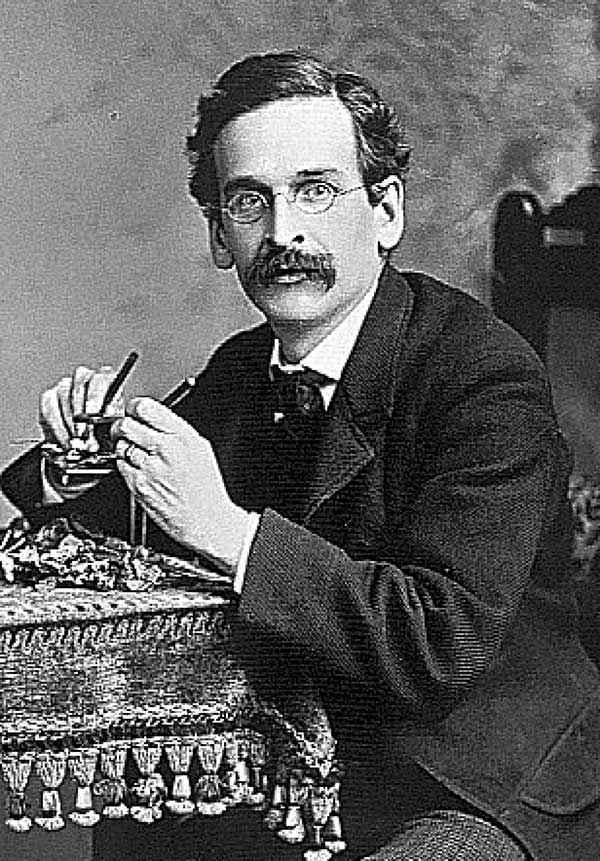

There may be no historic figure more deserving of the title of “Rhode Island Distinguished Naturalist” than William Whitman Bailey. First chair of the Natural History Department at Brown University, field trip leader, author of books and journal articles, private school teacher, artist, and poet, Bailey inspired a generation to the study of botany at a time when this pursuit was mostly considered frivolous.

William Whitman Bailey was born on February 22, 1843, at West Point, New York, where his father, Jacob Whitman Bailey, was professor of chemistry, mineralogy and geology. On July 28, 1852, William Bailey was with his family aboard the steamer Henry Clay when it burned and sank off Yonkers, New York. In the confusion, seventy people perished including William’s mother and sister. Long after the event he wrote, “After the dread event and consequent shock I never regained my original tone.”

Shortly after the death of his father in 1857, William was sent to Providence, Rhode Island, to live with an uncle. He entered University Grammar School and in 1860 became a freshman at Brown University. Although he left college with his class, he did so without a degree. In 1862, he enlisted as a private in the Tenth Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers, a unit established for three months’ service to provide additional manpower for the defenses in Washington, D.C.

Bailey occasionally visited a brother, Professor Loring W. Bailey, who held the chair of chemistry and natural science at the University of New Brunswick at Fredericton, and would at times assume his brother’s duties teaching chemistry, physiology, and comparative anatomy. In 1866 and 1867, he was assistant chemist in the Manchester Print Works, Manchester, New Hampshire, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston. Up to this time he had not been interested in botany, regarding work in chemistry to be his ultimate goal, but while in Boston he became a student of Dr. Asa Gray, at Harvard. In 1867, Bailey heard of the need for a botanist on the United States Geological Exploration of the 40th parallel, led by Clarence King. With Dr. Gray’s recommendation, Bailey joined the expedition, and from that time devoted himself to botany.

After the Henry Clay catastrophe, Bailey suffered from poor health the rest of his life, and in the spring of 1868 was forced to leave the 40th Parallel Expedition, being replaced by Dr. Sereno Watson. He later wrote, “I was with the party in Nevada about nine months when my health failed and I resigned. Still, for a tyro my work was not so bad. Watson told me that he adopted my sketch of the phytographic regions in his report.”

After his return, Bailey was variously occupied, including as assistant librarian at the Providence Athenaeum, teacher at several private schools, and part-time assistant at the herbarium of Columbia College, New York, with Dr. John Torrey. He also continued studying and teaching in the summer school at Harvard College, but his botanical career became established in 1877 when he started a private class at Brown University. It was the first botany class taught at Brown, and Bailey wrote, “At the end of the season I was voted thirty dollars, and was tempted to go on by the title of instructor and the advanced pay of fifty dollars for the season of 1878.” At first, the University’s support was meager. Bailey was required to sandwich his class “in between the older studies, in such lacunae on the schedule as remained after the others had chosen their hours.” He also had to meet wherever space could be found, including his own boarding house, and had to rely on the donation by “a few personal friends” of ten dissecting microscopes. As he described years later in The Brown Magazine, “a request for the purchase of any kind would have shaken the college cosmos.” He was, nonetheless, able to bring his class on field trips to well known Rhode Island collecting spots including Abbott’s Run, Diamond Hill, Snake Den, and Limerock.

Bailey supplemented his income by teaching botany at Miss. Abbott’s School and by offering private lessons to groups of interested individuals. In 1880, Rowland Hazard proposed to pay his transportation and a small stipend to conduct a class in Peace Dale. Bailey gladly accepted, writing in his diary: “There are five including Mr. H. in the class. They pay my way up and back besides the regular amount, and meet me at the train with a carriage. They give me a cup of tea before returning.” Bailey also convened meetings at his boarding house in Providence of naturalists and scientists including James Bennett, George Hunt, and Howard Preston, providing a forum for stimulating conversations on pertinent scientific issues of the day, especially Mr. Darwin’s ideas. In 1881, Bailey’s supporters prevailed on Brown University to name him chair of natural history (professor of botany), and curator of the herbarium, positions supported by the bequest of Col. Stephen T. Olney.

In October 1880, Bailey was commissioned by the Naturalist’s Bureau, Salem, Massachusetts, to write a Botanical Collector’s Hand-book, which, in 1881, became his first published work. Other books that followed included, Botanical Note-book (1894-1897), New England Wild Flowers and Their Seasons (1895), and Botanizing (1899), but his most beloved volume was Among Rhode Island Wild Flowers, published by Preston and Rounds in 1895. Here was Bailey at his best, writing in his poetic, non-technical style about plants and the places to find them in his adopted State. This volume remains today an important historic benchmark for students of the Rhode Island flora.

Bailey also contributed articles to journals including Rhodora, Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, Appalachia, and Botanical Gazette. Most important among these are two articles on Rhode Island plants. The first, entitled “Flora of Block Island,” is a report on the month he spent botanizing there with James F. Collins in the summer of 1892, and includes the first full accounting of the plants of Block Island during the period of heaviest human use, when “trees of any sort (were) extremely scarce.”

A second article, “The Old-time Flora of Providence” written in 1900, documents plant records collected by the city’s earliest botanists, along with his personal musings on the changes that had occurred during the intervening years. As examples, he noted that purple bladderwort had been recorded at Long Pond, noting “the locality has totally disappeared – as has the pond itself.” Also, how the cove at the head of the Providence River (now buried underneath Waterplace Park and Providence Place Mall) was formerly, “a natural estuary of tolerably pure water, in which one could bathe, and around which grew many littoral plants,” but which by 1900 he described as “putrescent” and “defiled by ashes and garbage.”

Brown conferred upon Bailey the degree of Ph.B. in 1873 and of A.M. in 1893, but his failing health compelled him to resign from teaching in 1906. He was honored with the title of Professor Emeritus and became one of the first recipients of a pension from the Carnegie Foundation, through a fund established to support retired scientists. He continued writing, especially for The American Botanist, for more than a decade and his last article, a treatise on hog-peanut entitled “Amphicarpaea”, was published after his death in 1917. Preceding the article, the editor noted how Bailey had been, “…a facile and entertaining writer on botanical subjects..”, and that his last article was, “a good example of the way a sympathetic treatment may make common things interesting.”

William Whitman Bailey was a consummate educator who always strived to make difficult concepts accessible for the layman. He wanted everyone to appreciate the natural world as he did, with reverence and humility. His daughter, Margaret Emerson Bailey, became a well known author in her own right, and in 1945 published “Good-bye, Proud World”, an autobiographical account of her childhood wherein she expresses an admiration for her father and his charitable style. She includes a conversation with him that may best define the life of William Whitman Bailey:

“Ever since I can remember, everybody’s felt they could come to you with questions. I can’t remember any walk we ever took when someone didn’t stop you on the street and want to know about a plant of some sort. I never knew you once to make them feel ridiculous, even when you had to say that what they asked about was just a common dandelion. No matter what it was, you treated ignorance with dignity.”

A fitting description for a most distinguished naturalist.