by Robert D. Kenney

In our report for the Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan, we showed that 36 species of marine mammals had been recorded in our estuarine and marine waters, and a few others were possibilities. Despite what might seem to some to be a surprisingly high diversity of species, only one of those species can truly be called a resident of Rhode Island—the harbor seal (known as the common seal in Europe). Harbor seals are the only marine mammal in the state where you can go to a particular location at a particular time and be reasonably confident of seeing wild marine mammals in their natural habitat. In fact, one of the “memorable events” we held to celebrate the R.I. Natural History Survey’s 20th anniversary was a program on seals that included a walk out to the largest known harbor seal haul-out in the state.

Seals are pinnipeds (“wing-foots”). Pinnipeds are marine mammals that are characterized by retention of all four limbs as flattened, simplified flippers. They are grouped into three families: the seals, the sea lions and fur seals, and the walrus. Pinnipeds are not as completely adapted to life in the ocean as are whales or dolphins, since all species must leave the water to give birth, either on land or on sea ice. Although Pinnipedia was once classified as a separate Order of mammals, recent evidence shows that they belong within the Order Carnivora (lions and tigers and bears, oh my!)—more closely related to the dog-like branch than the cat-like branch of the carnivore family tree.

Seals are pinnipeds (“wing-foots”). Pinnipeds are marine mammals that are characterized by retention of all four limbs as flattened, simplified flippers. They are grouped into three families: the seals, the sea lions and fur seals, and the walrus. Pinnipeds are not as completely adapted to life in the ocean as are whales or dolphins, since all species must leave the water to give birth, either on land or on sea ice. Although Pinnipedia was once classified as a separate Order of mammals, recent evidence shows that they belong within the Order Carnivora (lions and tigers and bears, oh my!)—more closely related to the dog-like branch than the cat-like branch of the carnivore family tree.

The population status of the harbor seal is believed to be relatively secure. They are not listed under the U. S. Endangered Species Act or on the Rhode Island state list, and are classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. The harbor seal population in New England has grown significantly since they were protected by the passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) in 1972. Mike Payne and Larry Selzer from the Manomet Bird Observatory in Massachusetts counted harbor seals between the Massachusetts-Rhode Island border and eastern Long Island Sound in the late 1980s and found only a few hundred. Only Fishers Island, New York consistently had more than 50 animals, with a peak of 101 in March 1986. In contrast, my graduate student Cheryl Schroeder estimated that the total number present in Narragansett Bay alone in 1999 was between 825 and 1,047. Dr. Jim Gilbert from the University of Maine has periodically counted seals hauled out on ledges along the entire Maine coast from aerial surveys. Between 1981 and 2001, seal counts increased from 10,543 to 38,014 (6.6% per year), and pup counts increased at an even higher rate of 14.4%.

Harbor seals were hunted by Native Americans for subsistence, then by early European settlers for oil, meat, and leather. In recent times, commercial hunting has never been of any great importance, but seals are commonly perceived as competitors for commercially valuable fish stocks. Bounties were paid on harbor seals in both Maine and Massachusetts into the 1960s, resulting in depletion of the population overall and its extirpation from pupping sites in Massachusetts. Harbor seals were also hunted for sport in the U.S. prior to passage of the MMPA. Strandings in Rhode Island are relatively common, averaging around 6–10 each year since 1990.

Harbor seals are taken as by-catch in a variety of U.S. and Canadian commercial fisheries, including gillnets, drift nets, long-lines, bottom trawls, midwater trawls, purse seines, trammel nets, fish traps, herring weirs, and even lobster traps. The most recent 5-year (2007–20011) estimate of average numbers of harbor seals killed annually in U.S. Atlantic fisheries was 407, mostly in gillnets. Other known sources of human-related mortality in the northeastern U.S. and Canada include boat strikes, entrainment in power plant intakes, entanglement in aquaculture facilities, and intentional shooting.

More is known about disease as a population impact for harbor seals than for other marine mammals. A relatively large number of diseases is known, and there have been several significant epizootics. At least 500 harbor seals died from Mycoplasma bacterial pneumonia in New England in 1979–80. The epizootic began in Cape Cod Bay in December 1979 and spread north along the Maine coast. The seals that contracted pneumonia were also infected with a strain of influenza A, and the hypothesis was that the influenza lowered their immune response to the Mycoplasma. There was a second, smaller epizootic in 1982 that killed only about 60 animals, which began in Narragansett Bay and was caused by a different strain of influenza A virus that normally is found in birds. And another influenza/pneumonia epizootic killed about 160 New England seals, mostly pups, in late 2011. Another virus that infects seals is phocine distemper virus (PDV), which was implicated in the deaths of about 18,000 harbor seals in Europe in 1988. PDV appears to be present in harbor seals in New England, but in most years does not cause increased mortality or even recognizable disease symptoms.

Description: Seals and sea lions differ in a number of anatomical characteristics, with the walrus often intermediate. Sea lions possess external ears, which are absent in seals and walrus. Seal flippers are completely furred with well-developed claws. The hind-flippers are oriented directly backwards with opposed soles, and cannot be rotated underneath the body for locomotion on land, which is accomplished by caterpillar-like wriggling. In water, seals swim via alternating, lateral strokes of the hind-flippers, while using the fore-flippers mainly for maneuvering. Sea lions have longer and at least partially furless flippers. The pelvis and hind limbs can rotate underneath the body for walking on land. In water, they swim by simultaneous flapping of the long fore-flippers and use the hind limbs more as rudders. Walruses walk like sea lions and swim like seals. Seal coats have little underfur, and a seal is insulated by a thick layer of blubber. Fur seals have dense underfur for thermal insulation and the least developed blubber layer, while sea lions have less dense underfur and moderately thick blubber.

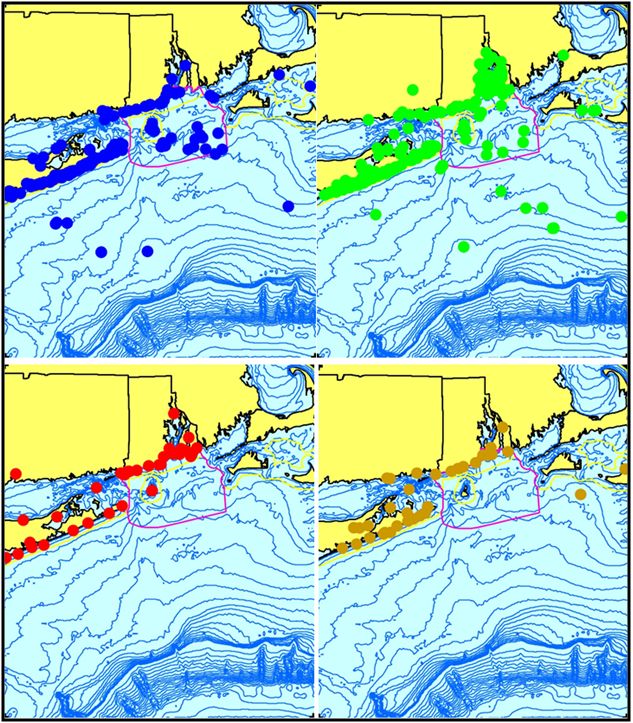

Aggregated sighting, stranding, and by-catch records of harbor seals in the Rhode Island study area, 1954–2005 (n = 507: winter [blue] = 158, spring [green] = 266, summer [red] = 48, fall [brown] = 35).

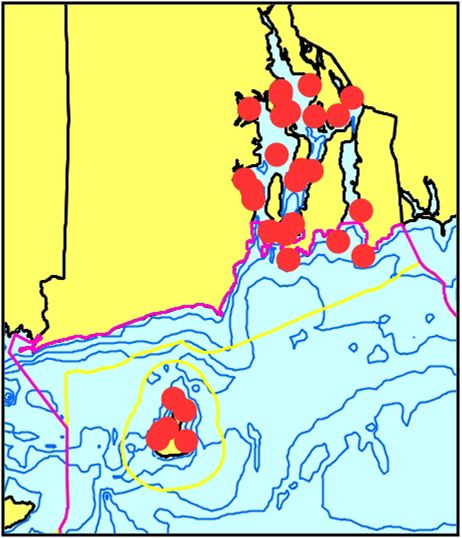

Harbor seal haul-outs in Rhode Island: 1966–1976, 1981, 1986–1987, and 1994–1999 (based on Schroeder, 2000, M.S. thesis).

Six haul-outs were identified in Narragansett Bay in the 1980s, with peak counts of 43 at the Dumplings off Jamestown and 36 at Rome Point in North Kingstown. The numbers of harbor seals in Rhode Island have increased dramatically since then. Cheryl Schroeder reported 21 haul-outs around Narragansett Bay during 1994–1999. The largest haul-out was a clump of rocks located less than a quarter-mile off Rome Point, with a maximum count of 170 animals. She also identified six harbor seal haul-outs at Block Island, collaborating with Scott Comings of The Nature Conservancy. The largest is at Cormorant Cove in the southwestern corner of Great Salt Pond. The other five are around the periphery of the island.

In Rhode Island, seals utilize different haul-out types around Narragansett Bay compared to those on Block Island. Nearly all of the haul-outs around the Bay are rocky ledges and isolated rocks that are mostly submerged at high tide. The exception is Spar Island, which is a man-made dredge-spoil island in Mount Hope Bay. At Block Island, there are several haul-outs on cobble and sandy beaches around the island, but the haul-out used by the largest number of seals is a wooden raft moored in Cormorant Cove, often used by 50 or more seals.

Coming next in Marine Mammals of Rhode Island: Harp Seal

Pingback: Harbor seals: RI’s resident marine mammal | Narragansett Bay Blog

Pingback: Explore Rhode Island’s Ecological Treasures › Providence, Rhode Island › Motif Magazine