by Robert D. Kenney

Illustration of a humpback whale, show the characteristic long flippers that are the basis for their scientific name—Megaptera novaeangliae (“big-winged New Englander”). (From http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/protected_species/marine_mammals/cetaceans/ humpback_whale_id.html; public domain).

Humpback whales were not scheduled to be the next installment in this series, but a lot of things have been happening recently, so it seemed like a timely idea to let them cut in line. [Editor’s Note: this was sent to us in December 2017, over a year ago, and we’ve been very neglectful in not getting it posted before now. My apologies to the author.] Number one was a change in their protected status. Humpback whales had been classified as Endangered under federal law since they were first listed in 1970 under the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969 (replaced by the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which is still in effect). The classification applied to the entire species globally. In September 2016, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) published a Final Rule re-listing humpbacks as 14 separate, identifiable, regional populations (Distinct Population Segments or DPSs in the legalese). Four of those were determined to be Endangered (Cape Verde/Northwest Africa, western North Pacific, Central America, and Arabian Sea) and one as Threatened (Mexico), and the remaining nine were determined not to warrant listing at all, including the West Indies DPS that occurs off New England. The reclassification was not without objections; the 62-page notice in the Federal Register included some 35 pages of responses to public comments received after the proposal was released. The new U.S. listing is much more in line with the IUCN Red List, which already classified most humpback populations as Least Concern. For the time being, humpbacks are still included as Federally Endangered on the Rhode Island state list, but that is now clearly wrong and the entire state list of rare animals is being revised and updated (with the R.I Natural History Survey having a role in the process). And they are still fully protected in the U.S. under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

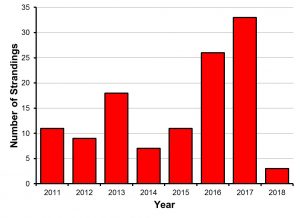

The other thing that has been happening has been an increase in the number of dead humpback whales washing up on beaches along the Atlantic coast or found floating in nearshore or offshore waters. When the numbers of dead animals of any marine mammal species increase significantly above the “normal” range, NMFS declares it to be an Unusual Mortality Event (UME), triggering a defined series of responses. An Atlantic Coast humpback UME that began in January 2016 is still on-going. From January 2016 through January 2018, 61 dead humpbacks were recorded between Maine and North Carolina (plus one in Florida in January 2018), which is a more than double the typical average of about 11 per year. The cause of the UME has not yet been determined. About half of the animals necropsied so far showed evidence of collision with ships, but there is not enough funding available for carcass retrieval and full necropsies on all that are discovered. Some previous humpback mortalities have been linked to exposure to natural biotoxins—both saxitoxin (produced by a dinoflagellate) and domoic acid (produced by diatoms). Even something like an increase in ship collisions could have an underlying natural explanation, e.g., whales changing their distribution in response to shifting prey patterns into places where they might be more likely to occur in heavily trafficked shipping lanes. Research is continuing, however in many cases a cause for a given UME cannot be determined.

Humpback whale strandings, Maine to Florida, 2011–2018

(2018 is only through the end of January). (Based on chart presented at http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/health/mmume/2017humpbackatlanticume.html)

Within the 62 dead whales counted so far in the current humpback UME, there were five in Rhode Island—two in 2016 and three in 2017. Note that the three in 2017 might really be only two. RINHS board president and Block Island resident Kim Gaffett is convinced that the stinky rotten whale on the beach at Mohegan Bluffs in September was the same animal as the really stinky, really rotten one that stranded at Ballard’s Beach in October—washed out by one storm and back in by another. If someone managed to collect good samples from both, DNA analysis will eventually sort it out. But it was the first one in 2017 that sparked the most interest and biggest response.

On Friday, 16 June 2017, a dead humpback whale was discovered on the rocks at Beavertail State Park in Jamestown. There was some concern at first that it was the whale seen earlier that week just off the seawall at Narragansett Pier, but it was soon clear that they were two separate whales. Mystic Aquarium sent a stranding response volunteer to identify, photograph, and measure the carcass (9.7 m long, or just under 32 feet), but they did not start a necropsy because that would make them responsible for the substantial costs of disposal. As Mystic, NMFS, R.I. DEM, and other groups discussed how to proceed, the weather turned bad and prevented any action for several days—while print, television, and digital media were filled with news of the stranding. About a week after the stranding, a popular blog called Newport Buzz published an article entitled “Block Island wind farm may have killed young humpback whale” (http://www.thenewportbuzz.com/block-island-wind-farm-may-have-killed-young-humpback-whale/12245). It turns out that the article was the same one written by Andrew Follett and published a little earlier by The Daily Caller, a conservative website founded by Tucker Carlson from Fox News and Neil Patel, former adviser to Dick Cheney. Other than simple statements like there being a dead whale on Jamestown, most of the information in the article was exaggerated, inaccurate, or just plain wrong (i.e., “fake news”). There was a flurry of emails around the Bay Campus, and a brief response correcting some of the most egregious errors, signed by myself and Prof. Jim Miller, a bioacoustics expert from the URI Ocean Engineering Dept., was sent to and subsequently published by Newport Buzz (http://www.thenewportbuzz.com/uri-researchers-block-island-wind-farm-highly-unlikely-to-have-caused-whales-death/12376).

The bottom line is that the Block Island Wind Farm (BIWF) did not kill that whale or any other whale. Dr. Miller and his colleagues have been measuring the sound produced by the BIWF turbines since they started operating in December 2016. At 50 meters away, the sound is so low that it cannot be detected above background noise unless there is no wind blowing and no boat passing in the vicinity. At any greater distance, a whale could not hear the turbines even on the quietest days. Pile-driving during construction of a wind farm does produce very loud sounds that are capable of disturbing whales or even causing hearing damage if they are close enough, but mitigation measures were in place to minimize potential impacts (e.g., no pile-driving during November–April when right whales are most likely to be present, protected species observers searching for marine animals nearby, and stopping the pile-driving if any whales are seen). Furthermore, the dead humpback on Beavertail in June 2017 could not have heard any of the BIWF pile-driving. A 32-foot whale would be about a year and a half old, so would have been born around January 2016. Pile-driving for the BIWF was completed just before Halloween in 2015.

Abundance and trends: Returning to the science, the number of humpback whales in the North Atlantic was estimated at almost 12,000 in 1992–93 by applying mark-recapture methods to the collection of photographs of known individuals. That number is known to be an under-estimate and is now 25 years old. The population also is known to be increasing, perhaps by as much as 6.5% per year. Current abundance is not known, but is surely much larger—at 3.5–6.5% growth rates a population (or a retirement account) doubles in 11–20 years. Humpback whale populations do show finer-scale separation into “feeding stocks” (see the Natural History section below), and the Gulf of Maine feeding stock presently includes about 1000 or more whales.

Humpback whaling in the North Atlantic began in the 1600s in Bermuda and continued into the 20th Century, peaking in the 19th Century. Many thousands were killed, seriously depleting populations. North Atlantic humpback whaling in the 20th Century was mainly from shore stations in Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, the British Isles, and Norway. Commercial humpback whaling was banned world-wide in 1966. The only North Atlantic hunting since the whaling moratorium began in 1986 (see the fin whale installment for more details) has been the occasional take by subsistence hunters in West Greenland or by a small, traditional fishery that has survived in Bequia, a small island in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, West Indies. Average annual human-related mortality from the Gulf of Maine humpback stock killed by fishery entanglements and ship collisions ranges from a few to almost ten, with entanglement the larger source. Fisheries involved in humpback entanglements have included pelagic driftnets, sink gillnets, and the ropes on lobster traps.

Description: Humpback whales belong to the rorqual family, like the fin whale, and are the easiest to identify of the rorquals. Adults typically range from 11 to 16 m in length. They have more robust, stouter bodies than fin whales, but are not as rotund as right whales. The body is black, often with some amount of white on the belly. The dorsal fin can be extremely variable in shape, from small and rounded to prominent and falcate or hooked. There is a distinct, rounded hump in front of the dorsal, and a series of projections along the ridge from the dorsal fin to the tail. Their most distinctive features are their flippers, which are very long (about a third of the body length) and usually white in North Atlantic whales, with a relatively smooth trailing margin and a series of prominent bumps (the “knuckles”) on the leading margin. The shape has been shown to reduce turbulence, and there is a company in Toronto testing wind turbine blades that are designed to be similar to humpback flippers.

A humpback’s rostrum is broad and flat with a somewhat rounded tip. There are rows of rounded knobs down the center and along the edges of the rostrum and on the lower jaw, so the head looks a lot like a giant dill pickle. Each knob has a stiff sensory hair (a “whisker”) in the center. There is also a prominent knob on the chin, which is covered by a clump of barnacles—acorn barnacles attached to the whale and stalked barnacles attached to the acorn barnacles (the subjects of an earlier blog: https://rinhs.org/animals/barnacle-stranding/). There are also barnacles on the “knuckles” of the flippers, the margins of the flukes, the edges of the head, and scattered in other areas. The flukes have a deep central notch and a concave trailing edge with a ragged or serrated margin, and their underside is patterned in black and white (from all black to all white, most often black in the center and white toward the ends). The patterns are unique and can be used like fingerprints to identify individual whales.

Natural history: Humpback whales occur in all of the world’s oceans, making some of the longest migrations known for any mammal between high-latitude feeding grounds and low-latitude calving and breeding grounds. North Atlantic humpbacks occur from the Caribbean Sea and Cape Verde Islands in the extreme south to as far north as Greenland, Iceland, Svalbard, and the Barents Sea. The vast majority of sightings in both the feeding and calving grounds are in nearshore and continental shelf waters, but the whales apparently migrate across deep oceanic regions.

North Atlantic feeding grounds are occupied from spring through fall, and are located in continental shelf areas. Humpbacks show strong matrilineal habitat fidelity. A calf learns the feeding grounds from its mother during its first year, and then tends to return to the same feeding areas each year. The result is a series of “feeding stocks” that can be genetically identified via mitochondrial DNA (inherited only through mothers), with very little interchange between stocks. Separate feeding stocks have been recognized from the Gulf of Maine, Nova Scotia, Gulf of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland/Labrador, West Greenland, Iceland/Denmark Strait, and Norway, possibly with further subdivision on even finer scales.

During the winter, humpbacks from all North Atlantic feeding grounds migrate south to calving and breeding grounds on shallow banks in the West Indies/Caribbean region, where they mix together. Because of this mixing, nuclear DNA (from both parents) shows fewer genetic differences between feeding stocks within a population. The peak calving and breeding season is January–March, with some whales arriving as early as December and a few not leaving until June.

Within feeding ranges, humpbacks tend to aggregate at specific locations where prey is most abundant. Humpback whale habitat use patterns and distributions on their feeding grounds are not static, but change over time. The distribution of humpback whales off New England has changed from year to year, following shifts in the relative abundance of herring and sand lance, the two principal forage fish species in the Gulf of Maine. Herring and mackerel stocks were severely depleted by commercial fisheries in the 1960s and early 1970s, and sand lance populations expanded greatly in response. Humpback whales shifted from feeding mostly in the northern Gulf of Maine to concentrating in Cape Cod Bay and east of Cape Cod. In the early 1980s, sand lance populations declined and herring began to recover. Humpback and fin whales declined around Cape Cod, and were nearly absent in 1986 (see the Recent Occurrence section below for more detail).

Aerial view of humpback whale bubble-net feeding at Stellwagen Bank off eastern Massachusetts. Two whales with their mouths wide open can be seen rising to the surface on the right side of the ring of bubbles. (Photo by the author).

Humpbacks are gulp-feeders like the other rorquals, but they display a much wider variety of feeding behaviors. They may lunge violently with the mouth open, or surface open-mouthed very slowly and gracefully. They also routinely use bubbles in feeding—either columns of large bubbles in partial or complete circles (“bubble-nets”), or large volumes of tiny bubbles that are apparently released from the mouth rather than exhaled through the blowholes (“bubble clouds”). Some whales add tail-slaps or other vigorous splashing to the feeding behaviors. There is evidence that specific feeding behaviors are learned from the mother.

Humpbacks will probably eat anything that is small enough to swallow and in a school big enough to be worth the effort, including both krill and fish. The principal prey species in the Gulf of Maine are herring and sand lance. In the northern Gulf of Maine, krill are also important prey. Off Newfoundland a small fish called capelin is a dominant prey species, and in the mid-Atlantic they likely feed on menhaden and other fishes.

Sexual maturity in both male and female humpback whales is reached at about 5 years of age on average, ranging from 4 to 9 years. Calving is strongly seasonal, with calves in the Northern Hemisphere born from January to March after a gestation period of about 11 or 12 months. Calves are born at about 4–5 m in length and reach 8–9 m by the time they are weaned (which is why we knew that the dead one on Beavertail was a yearling). Calves are fully weaned at about 1 year old, but begin to feed independently while still nursing at only 5 or 6 months old. The intervals between calves are usually 2–3 years, although females occasionally give birth in successive years.

Historical occurrence: Historical occurrences of humpback whales in the southern New England region west of Massachusetts were very rare and were unknown to most early naturalists. Glover Allen’s 1916 monograph (https://rinhs.org/animals/marinemammsofri1/) reported only one from Rhode Island, in 1836—“A note in the Providence Courier makes mention of a whale that had been seen several times off Newport, R.I., during the last of June. It was finally captured in Newport Harbor, ‘north of the asylum; it measures fifty feet in length, and is of the Humpback species and is supposed to be the same which was seen off Pawtuxet on Wednesday morning last’.” (The Newport Asylum for the Poor was built in 1822 on Coasters Harbor Island, which was turned over to the Navy in 1882. The original asylum building is now the Naval War College Museum.) The only more recent historical record from southern New England was a calf stranded at Matunuck Beach in South Kingstown in June 1957.

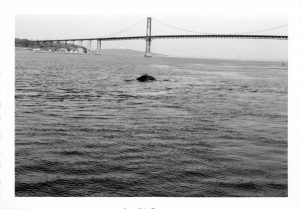

Humpback whale near the Mount Hope Bridge off Bristol, Rhode Island on 4 November 1968.

There was one additional historical record of a humpback whale that was not included in any scientific publication or database. I was a graduate student of Prof. Howard E. Winn (1926–1995) at GSO from 1978 to 1984. It was common knowledge around the lab that a humpback had been seen in Mount Hope Bay at some time in the 1960s. A box of photographs salvaged during the cleanout of Dr. Winn’s files after his death included an envelope with eight black & white prints of a humpback whale, labeled “Humpback; Bristol, R.I., 4 Nov. 1968.” One image clearly showed the whale close to the Mount Hope Bridge. The label on that photo gave the whale’s name as “Freddie,” but a newspaper article about the incident said its name was “Howie.” I guess we’ll never know which one was right.

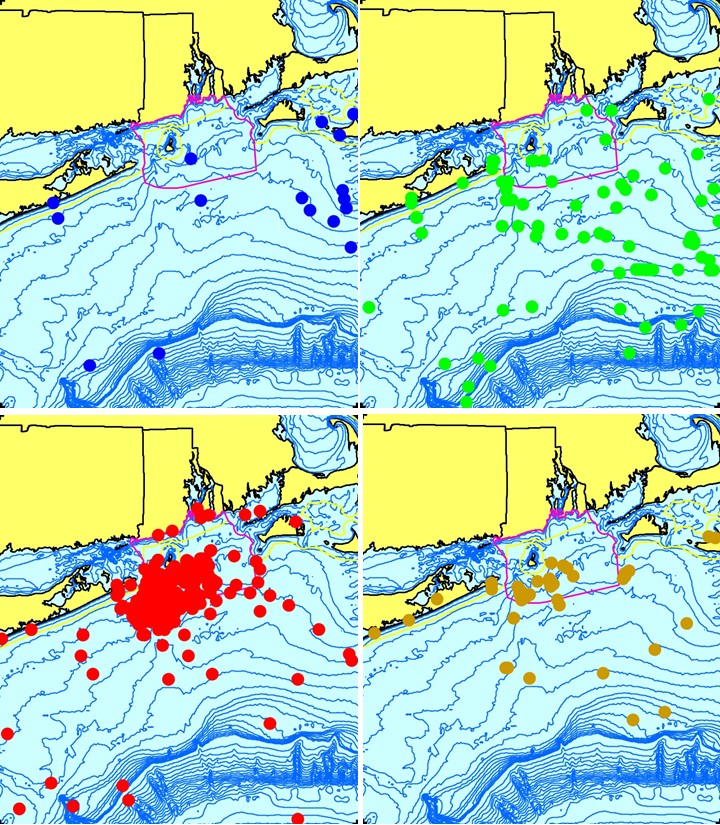

Recent occurrence: Humpback whales occur throughout the region in all four seasons, with many sightings from whale-watching boats concentrated south and east of Montauk in summer and late spring (see map). Including those data, 71.2% of records are in the summer, 15.7% in the spring, 10.3% in the fall, and 2.6% in the winter. Without the whale-watching sightings, the seasonal differences are less dramatic and the peak season switches to the spring (45.8%), followed by summer (33.6%), fall (10.3%), and winter (9.7%). Sightings are distributed across the shelf, especially in the spring. Except for the summer concentration from the whale-watchers’ data, the sightings tend to be more common in the eastern half of the area.

Humpback distributions in the Gulf of Maine have fluctuated markedly over the years, largely tracking patterns of abundance of their prey—herring, sand lance, and krill. In the years during the 1980s when humpbacks were scarce off Cape Cod, there were numerous humpback sightings between Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard by Montauk and Galilee whale-watch boats. The peak year for sightings from the Montauk boat was 1987, with 63 sightings (compared with 2 in 1986 and 9 in 1988); 1987 was also the best year for the Galilee boat. In 1987, the whales targeted by the whale-watching boats slowly shifted eastward over the course of the season—from near Montauk and Block Island to near Martha’s Vineyard. Sand lance populations in Cape Cod waters subsequently recovered, then went through another decline and recovery in the early 1990s, closely tracked again by whale sighting frequencies in the same area. There was similarly another increase in humpback sightings off Montauk in 1992 and 1993, and less dramatically in 1994 and 1991.

After an absence in the Rhode Island stranding record for more than 40 years, there have been 14 scattered humpback strandings in the state since in 2001, with the increase over historical numbers that is probably related to the growing population:

- 22 June 2001 behind “The Breakers” in Newport

- 10 August 2001 at Sachuest Point National Wildlife Refuge in Middletown

- 3 June 2004 on East Beach in the Ninigret Conservation Area in Charlestown

- 6 July 2005 on Bailey’s Beach in Newport

- 14 June 2009 on Briggs Beach in Little Compton

- 21 August 2009 in Sakonnet Harbor, Little Compton

- 8 May 2010 at Camp Cronin in Narragansett

- 5 May 2011 at Lloyd’s Beach in Little Compton

- 20 July 2012 in the Point Judith Harbor of Refuge in Narragansett

- 17 March 2016 at Mansion Beach on Block Island

- 26 April 2016 at Hazard’s Beach in Newport

- 16 June 2017 at Beavertail in Jamestown

- 5 September 2017 at Mohegan Bluff on Block Island

- 3 October 2017 at Ballard’s Beach on Block Island

Aggregated sighting, stranding, and bycatch records of humpback whales in the Rhode Island study area, 1608–2007 (n = 611: winter = 16, spring = 96, summer = 435, fall = 63, unknown = 1). (from the R.I. Ocean SAMP technical report)

The average for the 17-year period was less than one a year, eight years had no humpback strandings, and there were four years with more than one—2001, 2009, 2016, and 2017. It is difficult to tease out patterns with such very sparse data, but over the longer term and looking at the broader region, the data suggest that the occasional peaks of humpback strandings in southern New England correspond to the years of peak abundance in the area. Those, in turn, are likely related to cycles of prey abundance over the entire feeding range of the Gulf of Maine stock. Unfortunately, we no longer have regular whale-watching records in the region after 1996, so it is not possible to do any detailed comparisons over the full time span. It does point out, however, why it might be a bad idea to construct hypotheses about short-term changes seen in “your own backyard” without looking at what is occurring across the entire range of the stock. A humpback whale could easily swim from the Bay of Fundy to Rhode Island Sound in only a few days, so changes in the numbers of sightings locally (up or down) actually might reflect changes in the habitat off Massachusetts or Maine.

Coming next in Marine Mammals of Rhode Island: gray whale